Three Men, Three Stories

Today on Specifically for Seniors, we're going to do something just a bit different. We have three guests who are here to tell you three completely different stories about parts of their lives. You've met two of them on previous podcasts, but they didn't have the time to tell you the rest of their stories. The third is new to Specifically for Seniors, but it's the story of a part of American history that our generation cannot forget.

So make yourself a cup of coffee, sit back, relax, and let these three men tell you about a part of each of their lives.

Those of you who are regular listeners to specifically for seniors will recall Alistair Henry from our May, 2023 podcast. Alistair retired at 57, shed his possessions and went to live with the First Nations band in the Northwest Territory, then left Canada's North to volunteer, working with local NGOs. Those are nonprofit organizations in Bangladesh. He and his wife enjoyed budget pack packing for four months at a time in Central America and Southeast Asia in their sixties. In 2020, Alistair endured a double lung transplant. Alistair is back today to talk about the transplant and the work he is now doing as a Trillium Gift of Life advocate.

On November 22nd, 1963, a 26 year old junior duty officer was on duty at Bethesda Naval Hospital when the casket containing the body of Jack Fitzgerald Kennedy arrived from Dallas. You met that naval officer on this podcast on May 3rd, 2023. Sorel Schwartz today is a professor emeritus of pharmacology at Georgetown University Medical Center, and Senior Pharmacology advisor at the FDA Sorel is with us today as we near the 60th anniversary of JFK's assassination.

My third and final guest on today's podcast is Robert Norris. Robert's story is one that many of us who were draft aged during the Vietnam War era will have faced in one way or another. Robert is a Pacific Northwest, native Vietnam war, conscientious objector who served sometime in a military prison, an expat resident of Japan since 1983. He's the author of The Good Lord Willing, and The Creek Don't Rise. But, but let me let Robert tell you his story. We're talking to Robert from his home in Fukuoka, Fukuoka, Japan.

Book Availability: The Good Lord willing and The Creek Don't Rise https://www.amazon.com/Good-Lord-Willing-Creek-Dont/dp/180100000X

Sponsorship and advertising opportunities are available on Specifically for Seniors. To inquire about details, please contact us at https://www.specificallyforseniors.com/contact/ .

Disclaimer: Unedited AI Transcript

Announcer (00:00:06):

You are connected and you are listening to specifically for seniors, the podcast for those in the Remember When Generation,

Announcer (00:00:16):

Today's

Announcer (00:00:17):

Podcast is available everywhere you listen to podcasts and with video at specifically for seniors YouTube channel. Now, here's your host, Dr. Larry Barsh

Larry (00:00:38):

Today on specifically for seniors, we're gonna do something just a bit different. We have three guests who are here to tell you three completely different stories about parts of their lives. You've met two of them on previous podcasts, but they didn't have the time to tell you the rest of their stories. The third is new to specifically for seniors, but it's the story of a part of American history that our generation cannot forget. So make yourself a cup of coffee, sit back, relax, and let these three men tell you about a part of each of their lives.

Larry (00:01:33):

And welcome to specifically for seniors. Those of you who are regular listeners to specifically for seniors will recall Alistair Henry from our May, 2023 podcast. Alistair retired at 57, shed his possessions and went to live with the First Nations band in the Northwest Territory, then left Canada's North to volunteer, working with local NGOs. Those are nonprofit organizations in Bangladesh. He and his wife enjoyed budget pack packing for four months at a time in Central America and Southeast Asia in their sixties. In 2020, Alistair endured a double lung transplant. Alistair is back today to talk about the transplant and the work he is now doing as a Trillium Gift of Life advocate. Welcome back to specifically for seniors Alastair.

Alastair Henry (00:02:43):

Thank you, Larry. Good morning.

Larry (00:02:46):

Do you wanna tell us the background story of the transplant? What led up to it?

Alastair Henry (00:02:52):

Yeah. It was Christmas 2019. I was 74 years of age, and I was having trouble breathing. I'd been a smoker all my life pack a day, and I wasn't really too surprised. I was expecting at some point in life that the cigarettes would get me the, the addiction. I tried many times and I just resolved to, you know, say, okay, well this is gonna be my demise, you know? Anyway, it was about January, 2019. Yeah, January, 2019. I had trouble breathing. It was really bad. I felt like I was sucking through a straw. So I went to my doctor, saw a respirologist, and I was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Not, not lung cancer, but that, that's bad. That's gonna <laugh> high morbidity of three to six years. So I said, well, what have I got? I've got three years or six years. And they said, well, unfortunately, your fibrosis is quite advanced.

Alastair Henry (00:04:12):

You're looking at about 18 months. They put me on oxygen immediately, so five liters a minute. And you know, so obviously that was a, and then I realized, you know, we all have to die sometime. We're all gonna die sometime. But that gave me a best before date of about June 20th, 2018 months to do whatever I needed to do. And and I was okay with that because I, you know, I wasn't like 55. I, I was 74, so I accepted that. Went on the oxygen 24 7. So I was cutting this little oxygen cart around wherever I went. Had a unit in the bedroom set up generating oxygen. 'cause I had to sleep with the canula up my nose, and I had to go and lose a few. No. And, and, but before that, okay, and then I looked at everything and I thought, okay, what's on my bucket list?

Alastair Henry (00:05:15):

That really is the only thing that is important. And it was to go back to England to say goodbye to my sister, my nephews and nieces and friends one last time. And so I did that in August, 2019. I went to England with my wife, three children, three of my grandchildren. And we had a big party. Some of my nephews and nieces came in from London, France. And it was about 25 of us at this restaurant. And it was a wonderful, joyous occasion. You know, I was just celebrating my life. And I wasn't negative about it at all because I just figured, you know, I'd had a good life. And man, I did last, you know, I was 74. Anyway, I came back to Canada and realized that my fibrosis was progressing because I had to go from five liters of oxygen a minute to seven, to eight to 10 to 12.

Alastair Henry (00:06:21):

So, come around Christmas time, I was just coming to grips with everything, you know, thinking, okay, this is the last Thanksgiving, my last Christmas, last birthdays, last time I'd see these friends, and the last of everything. And I was okay with that. I had a sort of Buddhist mentality, Larry, that let me accept what is unconditionally. I wasn't angry, regretful, or looking to blame. I just accepted it. And my wife did too. We just accepted that this was our time. You know, I figured there's a lot of people gonna die before me, but they don't know it yet. So I was fortunate in that I knew and I could prepare and I could gauge it because of my <laugh> increase in my oxygen intake, you know? Anyway, it was about Christmas when my children said, dad, how about a lung transplant? And I said, you gotta be joking at my age, a lung transplant.

Alastair Henry (00:07:26):

There's no way. And my doctor hadn't mentioned it, so I, I tackled him about it. I said, what about a lung transplant? Is that possible? And he said, well, usually after the age of 70, you know, people got diabetes, high cholesterol, heart problems. But I got checked out and I was iner, health <laugh>, other than the fibrosis, I had to lose a little weight. So I had to go to physio for a couple of months to get my body mass index, you know, down to a certain level. But anyway, I went on the wait list in June, 2020, and after three false calls to zip up, because you've gotta, I was fortunate that I live in London, Ontario, just two hours away from the Toronto General Hospital, which is the hospital in Canada, in Ontario that does the lung transplants. If I'd have lived further away, I would've had to have gone and lived in Toronto, because you need to be within two hours for the operation.

Alastair Henry (00:08:37):

So anyway, I zipped up the high highway <laugh> going in there, but that was weird because I'm thinking, you know I may not get off the operating table. Right? You know, I don't know, 5% don't. And I thought, well, at my age, there may be complications, but I was okay with that because I figured I'm gonna die anyway. You know, because that's what my children said when they, they said about the lung transplants. And I said, oh, I don't know. It's you know, it's highly, highly invasive and it's very dangerous. I might die on the operating table. And when they said, well, you're gonna die anyway, dad. That was the turning point. That's when I decided, oh, I'm gonna have the, I'm gonna go for the lung transplant. Anyway, cut. Long story short story short, Larry, September 3rd, 2020, I had went into the operating room, came out with these new lungs. So that's over three years ago now. And they've been wonderful.

Larry (00:09:39):

What was your recovery like? Must've been tough.

Alastair Henry (00:09:42):

No, it was, no, it blows my mind. I went into ICU for two days because you got all these tubes, all these drain tubes sticking outta your ribs because they go into your body cavities to get rid of all the fluids and stuff, you know, because the lungs are they're encased in a pleura. So they go in and it's separate than the rest of your body. So the rest of your body is, because they break your, they snap your stern sternum, yeah, they push that back. They take your lungs out, cut 'em all off, put the new lungs in. So the bronchus up and everything, you know, put it all back stitch right across. So I was in ICU for two days, and then what they call step down, which is like a halfway house <laugh>, just to help you continue your recovery. And then after eight days, they discharged me and they said, no, hospitals are facet people. You're not sick. And I said, I'm not. I said, no, and you are healthier at home because the hospital's full of bugs, all sorts of people here with viruses and bacteria. Oh, sooner you get home the safer you'll be. It's not weird. Anyway,

Larry (00:11:08):

You make it sound like a car repair,

Alastair Henry (00:11:11):

<Laugh>. Well, it was in a way, you know, I, I, I just had one little wrinkle, and that was a problem. Every three months I had to go in for a bronchoscopy for the first three months. Bronchoscopy is where they go right into your lungs, take out a couple of little snippets, tissue. I think they take 10 samples just to ensure that the body isn't rejecting or there's no infection. And when they went in, there were little bit of a problem. They, they nipped the pleura, which caused one lung to collapse. It's called pneumothorax. Anyway, I went back in and everything's fine. So that was three years ago, and I've been perfect health since <laugh>. The other thing is, back in 2000, I'm a writer, huh. As you know, I started writing a book in 2016 a historical fiction romance novel, largely based upon early memories of growing up in England, because the world has changed so much.

Alastair Henry (00:12:19):

And I wanted to use all of this strong characters. And you know, there were world War II vets wandering around Bolton with PTSD. I said, there were no mental health help back in those days. You know, they all lived at the Salvation Army. They got turned out in the morning and said, you know, come back for supper, but we don't wanna see you for the rest of the day. So they wandered around Bolton, and they were scary because they had all these weird, some mumble to themselves, some shouted, and some were angry. And, and as kids, you know, we were really scared, stiffer them. We, and, and even adults, we'd cross the road rather than, you know, confront them. Anyway, I had all these images in my mind, and I wanted to write a book incorporating all of that, plus the home children, I became aware that Canada shipped to 120,000 children under the age of 14 to Canada without their consent.

Alastair Henry (00:13:29):

They were orphans because Canada had a labor shortage. So these kids came to work as on the farms as laborers and as domestics, because nobody cared. They didn't have any parents. So it was a whole scheme they put together between the British and Canadian governments and the orphanages and homes in Canada. And it was a, it was diabolical. But in, in the history classes in Canada, they didn't teach about that. They didn't teach about the residential school problem or the Chinese head tax, you know, that's it. They try to rewrite history and say, oh, yeah, the colonial, you know, it was wonderful. Anyway, I wanted to make people aware, because most people aren't aware. And these kids were they were indentured to their employer, the farmer or the homeowner. You see all these great big homes in Canada, well, who looked after the babies, who cooked, cleaned, you know, who cleaned the woodwork, who cleaned out the fireplace.

Alastair Henry (00:14:45):

It was little eight, nine year old girls domestics from England. Terrible. And they weren't treated as human beings, you know, they were, it was terrible. Anyway, so I started to write this story, but I stopped writing because, well, what's the point? I hadn't finished writing, and I thought, you know I might as well just focus my attention now on the last 18 months of my life and forget about the book. Anyway, with a new gift of life, I began writing again, and I finished the book, and so now it's available. So I brought it into existence, and that's one of the wonderful things I did with my gift of life. And now I'm talking to you too, about everything,

Larry (00:15:34):

And that was one of the gifts. And your other gift is working as a Trillium Gift of Life advocate. Tell us about that.

Alastair Henry (00:15:46):

Yeah, well, the, you know, as I said, Larry, I told you a little earlier, I was very lucky. Every three days, somebody on the wait list dies. There's just not enough organs being donated. And people, you have to register to be a donor in, in Ontario anyway, in other parts of the world. No, it's mandatory. You have to opt out. But in Ontario, you have to actually register. And it's sad. And I just feel that I was so fortunate that at my age, you know, I the lungs became available and I got them. So it's, it's a way to give back. So I tell people my story because I say, you know, had my donor not registered as a donor, I, I wouldn't be here. I mean, I'm breathing through his lungs, and this is what people don't realize. The lungs will never be mine.

Alastair Henry (00:16:52):

They're, they're a different DNA, they've been inserted in me, and I'm taking medications to make sure my immune system doesn't reject them. But, oh, man, could you imagine how grateful I am every day? Every breath I'm breathing through these lungs. So what I do is I advocate, I tell people, and I encourage them to sign the, you know, the organ and donor register. And I, I do things. I have this little gift of life PowerPoint presentation I give to community centers retire, whatever, whatever I can. And I'm part of the team with Toronto General Hospital that, to put this presentation to schools. This is for children in grade 12. Because it's the young people that haven't registered, I mean, they don't think they're gonna die, right? So, and a lot of superstition, they think, well, I don't wanna attempt death. You know, there is, there's a lot of people say, oh, no, I'm not gonna do that. And so, you know, we miss out.

Larry (00:18:08):

Alistair, thank you for sharing your story. It's inspiring. I hope people who listen to this will sign up for an organ donation registry here in the States as well. Thank you again for coming on specifically for seniors and telling us this part of your story.

Alastair Henry (00:18:37):

Thank you, Larry. It was a pleasure.

Larry (00:18:40):

On November 22nd, 1963, a 26 year old junior duty officer was on duty at Bethesda Naval Hospital when the casket containing the body of Jack Fitzgerald Kennedy arrived from Dallas. You met that naval officer on this podcast on May 3rd, 2023. Sorel Schwartz today is a professor emeritus of pharmacology at Georgetown University Medical Center, and Senior Pharmacology advisor at the FDA Sorel is with us today as we near the 60th anniversary of JFK's assassination. Welcome back, Sorel.

Sorell Schwartz (00:19:33):

I'm glad. Excuse me. I'm glad to you.

Larry (00:19:36):

Sorel. Take us back to that evening, 60 years ago. What were you doing when you were advised that JFK had been assassinated?

Sorell Schwartz (00:19:47):

What I was doing I was at the naval station by, at the Naval Medical Research Institute in Bethesda. Just a little clarification the National Naval Medical Center which is now the Walter Reed military Medical Center, the National Naval Medical Center was comprised of component commands. One of which the major one is the Bethesda Naval Hospital another of which is the US Naval Medical Research Institute. I was a I actually had just been commissioned and in the Navy for three months. And one of my collateral duties outside of being a a laboratory investigator was to, as all officers have at one time or another it's called the Duty Watch Show, where in the off hours, you have the duty of making sure making sure that the place doesn't fall apart.

Sorell Schwartz (00:20:58):

And this for the whole, for the whole medical center. So during the day I was in my, in my lab, I was informed by a colleague about the assassination or, or the attempted assassination at that time. And then we were all together in my department director's office as we listened and, and finally heard that, that he had died later that day at five o'clock in the afternoon. I did not have, I was not assigned and the duty watch for that day, excuse me. But I was waiting for my wife to pick me up to take me home. And I got a, a message from the Duty Watch at the Naval Medical Research Institute that they needed someone to add on to as a duty officer for the day, because they were bringing Kennedy's body, though.

Sorell Schwartz (00:22:03):

So I ended up joining the Auto Duty officer. One thing I learned in my 30 days of indoctrination was commissioned, is that you have the duty. When you have the duty watch, you have pretty much, you're put pretty much in charge of things. So you can imagine that with the president's body being brought there for autopsy there would be a lot of brass there, and there was a lot of brass there, enough to start a scrap yard. But they had they had just their their own responsibilities and the other duty officer had the responsibility of just making sure that things flowed right. Interestingly, and this is a rather important point, is that we had very little specific information. We knew that the president's body was being brought to Bethesda for autopsy.

Sorell Schwartz (00:23:11):

An ambulance had been sent out to Andrew's Air Force Base not to the specific purpose of, of bringing his body back but just for the, the purpose of anybody on board Air Force one who might have needed some type of emergency medical care. And and so I kept on getting calls from the administrative officer. The administrative officer of the medical center is like is like the COO, the commanding officers, this CEO and the administrative officers like the COO. And he was asking me if I knew how the president's body was being brought to Bethesda. And I, I told him that we were assuming it was gonna be brought by helicopter. 'cause Anytime the president comes in for physical exam or something like that, that they come in by helicopter. And this wasn't for physical exam, obviously, but we thought it was gonna be, it was gonna become by helicopter.

Sorell Schwartz (00:24:19):

So we had the Helo court ready. But we couldn't get any information. The Secret Service person who was at Bethesda could give me no information. 'cause He had no information, and they didn't have all the, you know, fancy communications like they have now. So I turned on the office television set, and and as I turned it, as the picture came up, literally they were loading the casket onto that Navy ambulance. And so I now knew how the how the casket was coming. And I, I phoned up to the administrative officer to tell him that the casket was coming by ambulance. He says, how did you know who told you? And I said, I saw it on television <laugh>. So that, that's somewhat of ironic. When, when the LANs arrived, which is about it's about a half hour drive from Andrews Air Force Base.

Sorell Schwartz (00:25:30):

In the in the LANs were Mrs. Kennedy, Jacqueline Kennedy Robert Kennedy and a couple of other people who were who were obviously Secret Service agents. We were we had a very large crowd on the base. People had found out from the rip by radio, obviously, or television, that they were bringing the president's body to, to Bethesda. And so we had well over a couple of thousand people on the on the base. And the security wasn't like it is today. I mean, you could go on and off the base at Will today. That never happened. But they so we had, we didn't have a large crowd control problem mainly just to keep them out of people's way, but we didn't have any concerns about behavior or anything like that.

Sorell Schwartz (00:26:38):

Mrs. When Mrs. Kennedy got outta the got outta the ambulance walking toward the entrance to the to the hospital, and I was about six, eight feet from her walking, walking backwards, and the whole, the whole purpose of which was to make sure that nobody ran stood in front of her to take a picture. But just when it went a lot of press bothering her, well, in fact there were, there was very little press in in in fact, I, I, I saw just one person who identified it as a press photographer. Other than that it's not like it would be today with cable television. You, you'd probably have like dozens of recorders and cameras around, but there, there was no press, literally no press there. And that's wor out by the fact that there's, there's very there's very little, if any, photographic evidence of what went on with be dozen.

Sorell Schwartz (00:27:50):

Mrs. Kennedy was still wearing the magenta or strawberry colored suit in her suit where the president's head would've been in her lap, was, was stain with blood. And but her stockings were almost stiff with dried blood on them. So she had obviously clearly was in, in this traumatic in the middle of this traumatic attack on, on her husband. She was I mean, she was well controlled. I mean, she had a stoic smile on her face, but there was there, there was no out route signs of of disturbance. She didn't have to see it to know it was there. Then what happened after this is sort of what has complicated some things. We we had a, a guard, a guard truck, and you know, it was like a, a a, you know, a semi-truck.

Sorell Schwartz (00:29:09):

And, and that the other duty officer and I, and then the military the military honor guard, which is made up of members of the, the four services air Force Navy, Marines, and they were on the back of the truck. I was sort of, I was on the running board. And I a department of Defense Guard was driving and the other duty officers inside. And we rushed to get the to get the coffin to the morgue and unloaded before again, we didn't know really if how much press was there. And we did not want a lot of press coverage on just moving a coffin and so forth. It just was you know, it was just a matter of of, of that taste. Even today there's a limitation in how much they allow unloading service, seeing servicemen who have been killed and by unloaded from transports. Lemme,

Larry (00:30:33):

Let me take you back just one step before we go any further. There was an interesting story you told about setting up the perimeter and something about a rope.

Sorell Schwartz (00:30:46):

Oh, well, oh, yes. Well, we, we, we had taken a rope, which is a fairly fairly dirty because I'd been on the back of the truck. And and we used it just to rope off an area so that people came around back there that it just showed where they had to stand. So so we roped off this perimeter and you may be, you may be referring to what I called that at, at the time, the, the uniform of the day that I had is called dress blues which are, which are black had the wearing of gray gloves. And, but the rope was so dirty. I I just didn't, I took my gloves off. I never ruined them. And then when the guard, honor guard was unloading the casket I stood at the tension and saluted, and I just glanced up and, and saw my hand, which is absolutely covered black with dirt from having handling the, the rope. And for some reason, I, I, I had this this thought that here I am on this awful day, and I'm saluting the president, and my hand is dirty, my hands, I should have clean hands saluting the president. That's, that's the type of thing that run through your mind at, at those times. But I think that's what you were, yeah. What you're referring to.

Larry (00:32:27):

I thought that was a very touching part of the story.

Sorell Schwartz (00:32:31):

Well, it it's something I re I remember, I, you know, in, in all of these things that no matter, this is 60 years ago, but you know, there, there are are, are two images that still are really burned into my mind. One was Mrs. Kennedy in her blood stained outfit outfit. And the other was my hand, which was so dirty. I mean, that those, the images I carry from, from from that day, I can still see my hand and how dirty it was. But before, before that there was an issue before when we first got to the morgue we were there and the analyst was supposed to be behind us, but it wasn't. And two cars were behind this. One was the president's Air Force military aid, general Chu, and the other was the commandant of the military Army Commandant of the Military, district of Washington general, I think it is.

Sorell Schwartz (00:33:58):

Well if I, if I recall his name. And we we didn't know what happened and where the, where the ambulance was. And so we almost got into a little bit of trouble. 'cause General McCue was somewhat touchy that night. Asked us if we knew what the hell we were doing, and we gave a response, which is not the response, not the type of response that a junior officer gives a general officer. And so he was, he was getting out the general accused, getting out about to come about to say, who do you think you're talking to? But he didn't quite finish it because general LI think that was his name who outranked him by one star said, Hey, general let 'em do their job.

Sorell Schwartz (00:35:10):

And so we, we probably escaped getting put on a report or some other type of disciplinary action, because he was quite annoyed with us. And what had happened was at, at the, at answers, the the Navy driver of the ambulance was replaced by a secret service driver. So by the, when we said that we were gonna go to the morgue our truck took off, the two general's, cars took off and the ambulance didn't take off because there was a crowd around it, and he didn't know the way to the morgue. So we came back and we did this did this all over again. During the, during the time when we were trying to find out what happened, I had made a comment that I can't believe we've lost the body of the President.

Sorell Schwartz (00:36:18):

And, you know, they guard, you know, everybody chuckled then, then we realized, okay, the no time for gall's humor, but that turned out to be something more significant than just a, a comment because what, what transpired in this subsequent years in in 1981, a, a book published by David Lifton called The Best Evidence in which it's claimed that there were actually two caskets brought to Bethesda. And one had been surreptitiously it had contained the body of the President, had surreptitious even taken somewhere in order for as he called them surgeons, to make adjustments in the president's head to coincide with the theory of of where the attackers were over the, where the alleged more than one assassins were this this, even to today, you can do it.

Sorell Schwartz (00:37:44):

I see it on the internet. There's still this discussion going on. What bothers me is one of the reasons I'm sort of willing to, to do this interview is that you know, 60 years ago, I probably, well, not probably, I'm sure I'm one of the few living survivors of of the time there having been a witness to what went on I know I knew that all of this business by the conspiracy is to to modify the president's body and so forth was just it was just a lot of bss. I told you that the that the administrative officer repeatedly called me to asked me what's happening, when, where is the where, when is the body arriving? And so forth. If there was some other something else going on where a body was being brought to a back gate as was alleged and and all of these machinations the administrative officer wouldn't have been calling me to find out what's happening, and he would've known, well, what's happening since he was in charge of running everything.

Sorell Schwartz (00:39:13):

So but the farther we get, the farther we get away from that date, the farther we get away from the also the truth about what happened on the date. And like I say, there's, if you look at all the documentaries that have been made on the Kennedy assassination, there's nothing about what went on Bethesda. But there's plenty of what went on Bethesda Bethesda by people who weren't there. The, the, the one accurate description of what went on when we, when we had lost the body, when we didn't, when the ambulance didn't follow us to the morgue, was in William Manchester's book, the Death of a President, where he he very accurately described what went on while we were trying to figure out where the ambulance was. And he had gotten that from interviewing the Army's the first lieutenant who was the army officer in charge of the honor guard. That was his representation was was accurate but that, that was also used by some, as a, as a primary reference to show that there was a, there was a mix up, or, or, or, or there was an intended mixing up of ambulances and so forth. But like I say, I was there. I know exactly what was happening because I was part of it.

Larry (00:41:10):

When did the reality of the whole day hit you?

Sorell Schwartz (00:41:15):

That's a, that's a, that's a good question, <laugh>. It's funny that you know, you're, you're, you're in the midst of all of this and you know, you're just not, you're just not thinking about fact. The president of the United States was assassinated. What you're trying to do is to make sure that everything was running smoothly and getting a first a firsthand lesson on the, on the responsibilities of duty officers because I was brought on as a, as a second thought, so to speak I didn't have to do what the other duty officer had to do, was to stay there overnight. So after everything was all calm and all the people had left I was able to go home. And I woke up the next morning and, and then it, it just, all of a sudden I was thinking about being all a part of this.

Sorell Schwartz (00:42:25):

And my mind had convinced me that I had, I had just had some sort of a nightmare. But on the other hand, there were too many little details that, that were, were quite were quite clear. So my, my wife is still sleeping. And I got out of bed and I went to the, the door of the apartment, and I opened up the door of the apartment, and there it was laying open the Washington Post. And I looked down and, you know, and, you know, saw his picture. And, and I remember 1917 to 1963 under the under his name. Then as I've said before, that I was correct. I had had a nightmare, but it wasn't con you wake up from but that, that was an interesting question about when I, when it struck me, because actually up until that time, I had, I had not processed that, that we had a new president, that our president had been murdered that I had been involved in, in the, in the process of, of of helping Mrs. Kennedy, of getting them of, of getting the, the, the caskets and women, all of that stuff.

Sorell Schwartz (00:44:03):

Just, it just, you know, it was it, it was that moment that I, I, I just had to realize and it, and it took me a while really to to realize this, and I thought that I mean, I had, strangely enough, exactly one month earlier been at the National Academy of Sciences where he, he gave the principal address for the hundredth anniversary of National Academy of Sciences. So I had seen him it's the only time I'd ever seen him he made that when he gave that speech exactly. I'm pretty sure it was exactly went on thorough or

Larry (00:44:58):

Sorel, thank you for coming on. This is a part of history we don't hear about.

Sorell Schwartz (00:45:07):

Yeah, it's, it's, it, it, it, I have to tell you every time I've, I, I have in, in preparing my thoughts for this interview I, I, I went back on the internet on the web and, and looking at all of the conspiracy stuff that was it's there and it just, you know, 60 years later, it was just, it, it doesn't anger me, it frightens me. And then I think of you know, our current day talks about discussing about conspiracy. And I think that these things, just, these things have a life to them. They just don't seem to die away.

Larry (00:45:53):

Sorel, thanks again.

Sorell Schwartz (00:45:57):

My, my pleasure, Larry. I, I, I, I love, I I I, I love your, your podcast and and I'm sure that that the audience of this podcast well remembers November 22nd, 1963.

Larry (00:46:15):

Thank you again.

Sorell Schwartz (00:46:17):

Thank you.

Larry (00:46:18):

My third and final guest on today's podcast is Robert Norris. Robert's story is one that many of us who were draft aged during the Vietnam War era will have faced in one way or another. Robert is a Pacific Northwest, native Vietnam war, conscientious objector who served sometime in a military prison, an expat resident of Japan since 1983. He's the author of The Good Lord Willing, and The Creek Don't Rise. But, but let me let Robert tell you his story. We're talking to Robert from his home in Fukuoka, Fukuoka, Japan. So good evening, Robert, welcome to specifically for Seniors.

Robert Norris (00:47:12):

Yeah, thank you, Larry. Thank you for having me on the show, and it's good to see you, too.

Larry (00:47:19):

You grew up in the Pacific Northwest. Tell us about your childhood family life.

Robert Norris (00:47:26):

Well, yeah I was blessed to be born in a, a beautiful part of the country in the, the Redwoods of the northern part of California in Humboldt County. And I was born in 1951, and so that makes me 72 years old now, <laugh>. And basically we grew up outside of the town of Arcata, which at that time had a population of about four or 5,000, and we lived on the edge of this redwood forest. So it was really an idyllic childhood, you know, fishing in the local stream for six eight inch trout and playing baseball and going for long hikes and just seeing a lot of animals. And it was a wonderful childhood. And maybe you know, I was like one of those TV show children of the 1950s, you know, leave it to Beaver <laugh>, you know, Opie or one of those.

Robert Norris (00:48:31):

But along came the 1960s, and you know, there was trouble everywhere it seemed like, but still we were hidden away behind the iron, not the iron curtain, the redwood curtain, and sort of oblivious to the outside world. But even so there were a lot of things you know, changing even within our part of, of the world. And my mother ended up divorcing my father. And so I ended up having to move to a different town and lived with her. And, and my stepfather, she got married about a year later, and my father also remarried. And so I ended up from the original family, I had one brother and one sister. But after my parents got remarried, we had a whole bunch of new stepbrothers and sisters, and all told we had enough to make a baseball team <laugh>.

Robert Norris (00:49:25):

We had nine brothers and sisters, and I would spend the summers with my father and the school year at my mother's place. And well, like any other kid at that time, I was obsessed with baseball and basketball and played a lot of sports, and didn't really have too many problems. And except watching the TV every night, we were, you know, very much aware of the Vietnam War. And so by the time I turned 18 of course, I, I thought the war was wasn't my cup of tea, so to speak. But you know, how do you get out of having to, to go fight in war in a country that you've probably never heard of before? So at that time, and perhaps I was a bit naive, but the Air Force or, or the Navy, seemed like a, a good alternative in the odds of having to go directly to the front line of Vietnam would be heavily reduced.

Robert Norris (00:50:24):

And when I talked to the Air Force recruiter, he promised me the world, you know, I could play basketball all day long and have adventures in different countries around the world, and life would be great. And I bought it hook line and sinker <laugh>. And so maybe on the first or second day of basic training, I, I knew I had made a big mistake and fate intervened. And at the end of basic training, my job assignment was to be a guard for B 52 bombers. And so when I was sent to my first base, after receiving a bunch of training and how to use different weapons and so on and so forth, I ended up having to walk around B 52 bombers. And I was sent to a base in California near Sacramento. It was called Beal Airbase. And at that time, there was a lot of underground newspapers that were very critical of the war.

Robert Norris (00:51:23):

And, and talking about all the events that were happening there you know, the campuses erupting with demonstrations and particularly the Malay massacre news came, you know, it wasn't hidden from us at all. And, and I ended up getting involved with a couple of guys who were working on an underground GI newspaper. And you know, these short-haired hippies who only had a few months left before they were out of the service had been talking to a lot of the soldiers who had returned from Vietnam and reported their experiences and their thoughts and feelings and opinions. And I was also heavily influenced by the music at the time, you know, music by Bob Dylan and some of his lyrics, and Crosby Stills and Nash, and others who were protesting the war. And Kent State was probably the final straw for me. Anyway, shortly after Kent State, I was given my order to go to Vietnam, and I took a month off. We were given 30 days of leave before having to report to a base in Texas for further war training.

Robert Norris (00:52:37):

And in the end, I decided, I, I just can't go. So I had probably one of three choices go to Canada and probably never be able to come back to the States again, or refuse my order and, and probably face you know, five years or so in prison. And then or, you know, just go underground, might be another alternative. And so I ended up going back to the base and you know, I was called into my commanding officer's office and given a final order to go, and I refused the order. And so I was set to be court-martialed about a month later. And I was 18 years, well, actually 19 years old at, at this time. And at my court martial, which took about a whole day of deliberation, it all boiled down to how I had responded to that order.

Robert Norris (00:53:34):

And I was facing the military crime of willful disobedience to a direct lawful order, which carried a punishment of five years in prison. And and und or not not undesirable dishonorable discharge. And I was found not guilty of the original charge, but guilty of a lesser charge, which they called negligent disobedience to a direct lawful order. And the difference being, I never used the word no. When I responded to my commanding officer's order, I kept repeating the same sentence. I, I don't feel I'm mentally or physically capable of killing another human being. And during the whole day's deliberation that was the difference. And I was sentenced to six months. And so I served my time and got booted out of the service with an undesirable discharge and returned to society. And fast forward a couple years, I'd tried college a couple times, and tried playing basketball again.

Robert Norris (00:54:38):

But I'd had too many strange experiences and, and just felt kind of alienated actually. And so I, I ended up doing what a lot of young hippies of the time did on a search for identity, I guess you could say. I hitchhiked across the states and then bummed around Europe for a few months, and came into contact with a lot of other young hippie types who were backpacking around, and mostly Europeans. And I was amazed at the number of artists and musicians and painters that I came across. And, and I was so envious of their ability to speak three or four languages, and I could barely speak my own native language. And they all seemed to have fulfilled lives and exciting lives. And so when my money ran out and I came back to the States and hitchhiked back to the West coast again, I now had a, a kind of target, I I wanted to become a writer. And so that's when I first started writing and started out with kind of short dashes, short stories, and over four years or so of working different labor jobs and working mainly as a cook and saving my money, I, I ended up four years later returning to Europe and to Paris, and was all set to try and write a novel based on all my experiences. So, so that was the start.

Larry (00:56:09):

So did you consider yourself a hippie and embrace counterculture, the whole scene?

Robert Norris (00:56:15):

<Laugh>? Yeah. I, I could say like Bill Clinton <laugh>, I, except I inhaled <laugh> <laugh>. But yeah, I, I, my hair was pretty long. I had a beard and you know, I experimented with a lot of the things that everybody else was experimenting with. And, but yeah, speaking of hippie, when, when I returned to Europe, I was in Paris kind of heavily under the influence of Hemmingway and the expatriate writers from the 1930s and, and Jack Carac, Henry Miller, expatriate writers. And one day coming back from walking on, on the streets of Paris and just you know, observing life, basically. I came back to my rundown cheap hotel, and there were two men at the front desk trying to convey a message to the desk clerk. And one was in Iranian and another was in Afghan.

Robert Norris (00:57:16):

And they were trying to give a message to the desk clerk who spoke only French. And so I'd picked up a little bit of French by then, and I was able to give a crude translation. And the desk clerk seemed to understand, so these two men were just overjoyed, and they invited me out for a cup of tea. And so we became friends real quickly, and they invited me back to their countries. And so I was ready, you know, <laugh>, I'd never been to Iran or Afghanistan before, so I said, okay, it sounds like a good adventure. And we actually, well, I the, the Afghan traveled back by train, but I ended up going with the Iranian who bought a car in Germany and he could sell it back in Iran, you know, and cover the cost of, of the journey.

Robert Norris (00:58:01):

He, he and the Afghan were basically selling carpets and other ornaments and jewelry and, and artistic things for inflated prices in, in Europe. And they were making a pretty good living at the time. Anyway, the Iranian and I traveled the old hippie trail through well, we started in Germany and we went through Switzerland to the northern part of Italy, then through Bulgaria into Turkey, and had quite a few adventures in the high mountains of Turkey, where it was still at the end of wintertime. And it was pretty severe weather conditions, and the roads weren't you know, four lane highways, that's for sure. We escaped narrowly a couple of times, but we managed to make it into Iran. I spent maybe a couple months there, and then another month in Afghanistan and ended up in India. The whole trip took probably about 10 months or so, but when I finally ran outta money, and I was able to use the last of my money to get a, a flight cheap flight out of India, and landed back in Los Angeles with 25 cents left to my name <laugh>, and, and a severe case of reverse culture shock, <laugh>, <laugh> <laugh>. But those were my, my main hippie experiences. Yeah.

Larry (00:59:27):

And how did you end up in Japan?

Robert Norris (00:59:30):

Well, yeah, that's, I, I didn't plan it. That's definitely for sure. But those earlier experiences in Europe and then meeting so many really kind people on the road you know, on my round, the world journey. And I, I just had this dream that I, I wanted to live and work and study in, in a foreign country. And originally I thought, well, maybe Spain or, or Greece, someplace in Europe would be great. But I had a friend, a writer who was living in Hawaii and on the island of Maui. And after I returned from India, I spent the next four years basically working on the oil rigs as a cook, and ended up in a oil refinery. Can't, well, not, it was a construction site that was building an oil refinery in the high desert of Wyoming, a very isolated place.

Robert Norris (01:00:30):

There were about a thousand laborers who were building this oil refinery. And so I ended up getting a job there for about a year, became the head baker. And there was nothing to do but work. And so we saved up a few thousand dollars, and I'd been writing to this friend of mine, and he had an extra room, and he said, well, come on out. You can come here and, and, and work on a novel or whatever you wanna do. And so when I got there, we started talking about his books and whatnot, and he'd had more success in Japan than in America. He did okay with sales in, in the States with his books, but they were translated into Japanese, and he became very popular in Japan. And so he had been to Japan a couple of times and just had really good experiences, and he knew a couple of people who were working as English conversation teachers. And so he gave me the address of a friend. And so I contacted that friend and he said he could put me up until I got set up. And so I ended up going to Japan on a one-way ticket, and maybe about $300 in my pocket. But I, I found a, a job at a conversation school initially. And so it took a few years, but piece by piece, you know, I was able to work my way up. And you, you didn't know

Larry (01:01:54):

Japanese, you couldn't speak Japanese.

Robert Norris (01:01:56):

Yeah, the only thing I knew about Japan at that time was that the United States had fought Japan in World War ii, and I remembered reading those GI Joe type of comic books, you know, from the 1950s that had all these caricatures of the Japanese, with the soldiers, with the thick glasses and the, you know, razor heads. And, and that was basically my image of, of Japan. And once I arrived in Japan, I was completely fascinated by just the, the kanji lettering everywhere. You know, there's, at that time not so much English, all the billboards, everything. And, and I landed in Osaka, so there's a lot of people there. Being a country boy, it was quite overwhelming to the senses of just people. Sounds, noise, smells, everything. But it was fascinating, just fascinating. And I still, still enjoy it. <Laugh>,

Larry (01:02:50):

You, you got your degree from college in Japan?

Robert Norris (01:02:55):

Yeah. It,

Larry (01:02:58):

And went on to become a professor and a professor emeritus.

Robert Norris (01:03:03):

Yeah, that was quite a long story too. I <laugh> I could never have dreamed that that type of life would eventually become part of my life, <laugh>, when I landed in Japan, I had very little money, and I was basically working illegally, you could say, on a tourist visa. But I was working there and I, I ran into an American who had worked at the same conversation school and had quit the school and started his own school. This, this was the early 1980s, 1983. And Japan's economy was really starting to boom around then. And there was a, a great demand for English. And you know, even companies were doing a lot of research and development and opening up factories overseas, and they needed engineers who could speak English and, and communicate well in English with their factory workers.

Robert Norris (01:04:00):

And so even companies were setting up English courses. And I worked for a few companies. I worked for a couple of conversation skills and was basically in every type of teaching situation that you can imagine from, you know, one-on-one lessons to teaching five-year-old kids in groups of 20 to 30, and even conducting seminars with a hundred people or so. And, and so I ended up meeting my wife, a Japanese woman, and, and committed myself to becoming a, you know, permanent expatriate. And I got a, a sponsor for my visa and conversation, teaching is not a real stable type of job. And so I, I thought, well, if I could get a degree, a master's degree perhaps I can catch on with a university or, or a junior college in so I founded an American correspondence course, and this is way before the internet.

Robert Norris (01:05:03):

So we, I, it was a true correspondence course, you know, with the old letters, with the stamps on them, <laugh>. It took seven years to complete the course in education with a, a specialty in the teaching of English as a, a foreign language. And when I got my bachelor's degree I was able to find a job at a vocational school that specialized in English education, and they, the graduates would go on to work in hotels and, and travel agencies and putting their English skills to practical use. But the salary wasn't really so good and benefits were basically non-existent. But once I got the master's degree, which ended up taking about seven years from the time I started working full-time and studying at night in addition to Japanese studies I worked a bunch of different part-time jobs.

Robert Norris (01:06:02):

And one of the part-time jobs I found was at a women's junior college teaching once a week, and just fate, just once again, intervened in my favor. And just as I was getting the master's degree an open opening came up for a foreign full-time foreign instructor. I applied and had to compete with about 50 other people. But fortunately, the final step was an interview in Japanese, and I was able to pass that where my competitors kind of panicked, I guess, and their Japanese wasn't so fluent. And I was hired. And so because I could speak some Japanese, you know, or enough to do my job, I could participate in meetings and be a member of committees and do things like go out to high schools to recruit students and things like that. So my first full-time job started when I was 41 years old, and started paying into a pension fund and boom, you know, 25 years go by pretty fast. And I was suddenly 65 and time to retire. And <laugh>, here we are seven years later.

Larry (01:07:17):

So you're retired now from teaching?

Robert Norris (01:07:20):

Yeah, yeah.

Larry (01:07:22):

Do you ever look back and regret your original decision not to fight in the Vietnam War?

Robert Norris (01:07:30):

No, no. That was the best decision I ever made in my life, I think. And there were a lot of people who disagreed with me, of course, and, and you know, you just have to deal with the criticism and, and I was lucky enough, I, I suppose, yeah, to kind of segue into talking about my, my book and my relationship with my mother. I, I think I inherited a lot of her stubbornness, <laugh>, and she was a, a very strong, independent woman who was always supportive always you know, went out of the way and, and, you know, I caused a lot of grief for a lot of people, but she was always right there, you know, holding me up and supporting me. So yeah, I, I, I've never thought twice about it. I, I've always been one who, you know, whenever you come through to a fork in the road somewhere, you know, it's like Yogi Baris said, if you come to a fork in the road, take it <laugh>, don't look back.

Larry (01:08:44):

So the book is a tribute to your mother and your relationship with her.

Robert Norris (01:08:50):

Yes. Yes. Yeah. she died. Let's re

Larry (01:08:56):

Let's repeat the title for everybody. The Good Lord Willing and the Creek Don't Rise. Mento Memories of Mom and Me.

Robert Norris (01:09:07):

Yeah, it's a fairly long title and took to explain the title a little bit. The first part, the Good Lord Willing and the Creek Don't Rise. My mother used to say that all, all the time, and she picked it up from her grandmother and whenever she was facing some tough situation, or her kids were in dire straits of some sort. She would always tell us, you know, don't worry. It'll all turn out okay. And then the good Lord willing and the creek don't rise <laugh>, you know, then we'd all have a nice little giggle after that. And so she was a very optimistic person, and I thought, well, that phrase, you know, kind of describes her attitude towards life as, as well as, as anything, just keep your head up and good things will happen as long as the, the good Lord is willing and the creek don't rise.

Robert Norris (01:10:00):

Then the penal memories of Mom and me, I always liked the writer Lillian Hellman who was Dashell Hammett's lover. I don't think they ever got married, but they had a relationship for maybe 30 years or so, and during the, the, the thirties, forties, and 1950s. And she was part of the, the Hollywood group that was blacklisted and had to face the house, un-American Activities Committee. And you know, she was just a very strong independent woman herself and, and very liberal. And and in the 1960s she wrote three memoirs and, and the title of one was, was Pento. And she used that phrase, which is a phrase used in, in or a term used in art in to describe when a painter paints a certain scene, a kind of rough draft of something, and then changes his or her mind repents, so to speak, and then paints over that, and a completely new scene develops.

Robert Norris (01:11:10):

And Leland Hillman used this term as a kind of metaphor for memory. So as, as we age and we think back on our earlier experiences those scenes from our earlier life change from time to time. And so after my mom died a couple years ago, just short of her 95th birthday, I, I had all this correspondent from correspondence from years and years of letters and emails, and actually I recorded some of her stories about family growing up in the 1930s. They lived a life similar to the Joe's and, and the Grapes of Wrath only for her family instead of Oklahoma to Southern California. They started in North Dakota and ended up settling in Washington and Oregon on the Columbia River. And so all those earlier memories came flooding back to me when I was going through all the earlier letters and even the, the recorded audio tapes that we had a few videos as well.

Robert Norris (01:12:15):

And it seems like my memories for changed several times. And so I thought, Hmm, mento would be a wonderful expression to use there too. Yeah. So it's a tribute to her. And the, the way she was such a positive influence on my life to her, her, her grit, her her determination. She, in a time when it was very difficult for a woman to be financially independent she was able to forge ahead even after her divorce. She was always working, even cleaning rooms doing people's laundry, doing whatever it took to raise her kids until she got married a second time she was Catholic. And so when she married a second time, she was excommunicated from the Catholic church, and that had a a strong, you know, emotional effect on her. But she overcame that. And then it, at some point, her second husband did a lot of gambling and got into debt with thousands of dollars.

Robert Norris (01:13:24):

And so she divorced a second time, and she paid back all those gambling debts herself. And in her fifties, she took night classes to become qualified as a legal secretary, and she ended up becoming a legal secretary and worked until she was maybe 58 years old and retired with a, a nice little pension for herself. She even in her forties got a private pilot's license, and for two years worked as a, a fire spotter for forestry service in the Lake Tahoe area. And so she, she was very adventurous. She came to Japan about eight different times. We ended up taking a trip to Ireland one time to sort of search for her family roots. She was a Murphy. Her father's ancestors were from Ireland. And we ended up meeting maybe about six or seven distant cousins and just had a wonderful magical time in Ireland. And so when I think back on, on her and, and the life she led and the influence she had on me, and I, I just feel really blessed that this was my, not only my mother, but my best friend <laugh>.

Larry (01:14:38):

She sounds like quite a woman.

Robert Norris (01:14:40):

Yeah.

Larry (01:14:43):

IWI was reading over some of the reviews of your book. One stuck with me, Tom Nichols, journalist and author, said about your book, and I quote, Norris's story should be, must reading for today's students who think that the sixties was all about Woodstock and High Times. What do you think about that remark and your story and today's kids?

Robert Norris (01:15:11):

Well, I, I'm flattered that <laugh>, you know, he would think that my little, you know, book would be must reading, you know for historical purposes. Certainly a lot of time has elapsed since, you know, the Vietnam War, and we've experienced that and, and I've often wondered, you know, how is the Vietnam War being taught in, in American schools, particularly junior high school and high schools? And you know, if you go online to search for this kind of information, there are a lot of books, a lot of people have been writing memoirs, you know, that cover the whole gamut from soldiers who, you know, fought in Vietnam to those who came back with PTSD. And, and, you know, the, the born on the 4th of July type of fellows who, who became very strongly anti-war and you know, all part of the baby boomer generation.

Robert Norris (01:16:17):

And most of us are now in our seventies or eighties. And so there's quite a distance from the Vietnam War, and we've had so many wars in between. And, and every time it just, you know, it saddens me deeply that, you know, mankind never seems to learn. Look at what's happening today. I mean, what a horrible time to be young. I, I do gain some hope in the form of I've, I've read where a lot of Russian young men and even a few Ukrainians and Israelis have refused to fight and have become conscientious objectors themselves. And I, I just wonder, my God, the penalties they face are, are unimaginable compared to those that my generation faced. And, you know, conscientious objectors in the First World War were severely disciplined and, and a lot of them died in prison. And then the, in the second World War, it was, the situation was slightly better.

Robert Norris (01:17:29):

You know, a lot of them performed alternative service in the the CCC camps and, and whatnot. And by the time the Vietnam War came around, and especially my particular generation, you know, they had, the Supreme Court had ruled that not only could conscientious objectors be qualified in the religious sense, but also if they were sincere in their philosophical and moral beliefs and behavior, then a certain number were, were recognized. So the situation, you know, seemingly had improved in America, but in other countries you know, they probably just take 'em in the back, you know, yard and shoot them. And, and so I can't imagine the courage that it takes for young people from some of these other countries to, to do the same thing as far as young people studying about history. I don't have any direct experience that you know, is that their image really of, you know, were, was it just all smoking pot and, and listening to rock and roll music and going to places like Woodstock and much of the hippie generation imagery in the, the mass media, the movies and whatnot is kind of a caricature, it seems like to me, <laugh>.

Robert Norris (01:18:47):

But I haven't really had any direct experience, so I can't really say my only direct experiences with my own students here in Japan. And for several years I was responsible for teaching a, a class called American Culture in Society, which I had to teach in Japanese, but I often covered the 1960s and 1970s. And, and I used a lot of the anti-War songs that came out of those times. And, and this was during the Rock War too. And so there was a certain number of songs that came out with pretty strong lyrics protesting the war during you know, 2004, 2005 in Iraq. And my Japanese kids and, and some international students from China and Taiwan and the Philippines, Korea. They responded really favorably. And they were, we had some really good, serious discussions.

Robert Norris (01:19:50):

And so, if I can extrapolate from their experience to how young people in America are responding to the current situation you can see the thousands and thousands of people that are out there in the streets, you know, demonstrating now. And so I have a lot of hope for the young people, you know, that that's the nature of young people is to mm-Hmm. <Affirmative> protest, dissent, rebel against what the older nation, you know, it, it comes back down to it's the old men who, who make the wars, but it's the young men and women who have to go fight the wars, and that's just not fair.

Larry (01:20:30):

Yeah. I think

Robert Norris (01:20:31):

Everybody feels that

Larry (01:20:32):

I have four grandchildren and who are all about late teens, early twenties, that I worry about

Robert Norris (01:20:42):

Ah,

Larry (01:20:44):

Yeah. My experience. Do

Robert Norris (01:20:45):

You think

Larry (01:20:45):

That, Hmm.

Robert Norris (01:20:46):

Oh, I was gonna ask you, you know, is there any discussion in the States these days about bringing back the draft?

Larry (01:20:56):

Have Yout heard anything about that I haven't heard of? That's what I

Robert Norris (01:20:59):

Worry about. 'cause I, I've read a few articles where during the last few years, you know, they all volunteer armed services. They're not meeting their recruiting targets. And so, I mean, it wouldn't take much for Congress to reinstate the draft, and that's what I worry about.

Larry (01:21:19):

My experience was I was, I was in, in what was called pre Vietnam era 62, 63, I was given the choice of volunteering as a dentist retired dentist, or waiting until I set up my office and being drafted. So, <laugh>, you

Robert Norris (01:21:48):

Chose dentistry

Larry (01:21:49):

<Laugh>? I, no, I chose yeah, I think I better volunteer <laugh>. It might end up being a shorter period of time. And then we ended up my wife and I going to Vietnam about a dozen years ago.

Robert Norris (01:22:06):

Oh, oh.

Larry (01:22:08):

And going through the tunnels and as tourists.

Robert Norris (01:22:15):

Wow. Wow.

Larry (01:22:17):

Vietnam still calls it the American War.

Robert Norris (01:22:20):

Yeah.

Larry (01:22:21):

Yeah. So, did we miss anything? This was fascinating.

Robert Norris (01:22:27):

Hmm. I can't really think of much. You know, we could always have another conversation anytime <laugh>, maybe on lighter subjects,

Larry (01:22:36):

<Laugh>, I, anything would be lighter, but it, your life story is just fascinating as hell.

Robert Norris (01:22:47):

Yeah. I, I've been a a lucky man, A lucky man. <Laugh>,

Larry (01:22:51):

So, thank you. Huh? Go ahead.

Robert Norris (01:22:54):

Oh, I, I was just gonna say I've been such a lucky man, and, and I think a lot of that started from that first journey I took across the states into Europe, you know, I just kind of gave up my fate to the winds and whatever came, I, I was ready to accept it. And once I, I changed that attitude. Nothing but good has come to me over the years, you know? And so fear of the unknown is, is a normal thing. But I think I threw that out the window, <laugh>, and I've been very, very lucky.

Larry (01:23:29):

What you did takes a lot of courage.

Robert Norris (01:23:32):

Well, thank you. Just,

Larry (01:23:34):

Just letting fate determine what was gonna happen next. Yeah, I can, I can imagine a life like that.

Robert Norris (01:23:43):

Yeah.

Larry (01:23:43):

So, yeah. Thank you for sharing. Read the book <laugh>.

Robert Norris (01:23:47):

Hmm. Thank you. I'm sorry. Read, read the book <laugh>. But thank you for having me on, Larry. It's been

Larry (01:23:53):

A pleasure. Enjoy, and thanks for sharing.

Robert Norris (01:23:55):

Yeah. Thank you.

Larry (01:23:58):

Three men, three stories you've been listening to specifically for seniors.

Announcer (01:24:09):

If you found this podcast interesting, fun, or helpful, tell your friends and family and click on the follow or subscribe button. We'll let you know when new episodes are available. You've been listening to specifically for seniors. We'll talk more next time. Stay connected.

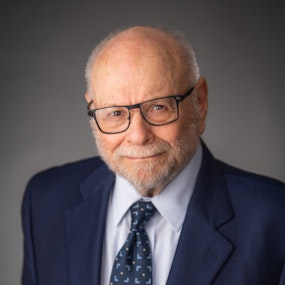

Sorell L. Schwartz, PhD

Emeritus Faculty

Sorell Schwartz is Professor Emeritus of Pharmacology. His areas of concentration include quantitative systems pharnacology and pharmacometrics; adverse drug reactions, human subject and clinical trial ethics, and causal assessment methods for drug and chemical injury. Research approaches are primarily through computer simulation of biological processes to aid understanding of those processes. His has focused on physiologically-based pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling and its application to such areas as exposure assessment, target-tissue concentration estimation for risk assessment, and the design of dosing regimens for experimental drugs. His most recent work concerns bio-mathematical approaches to understanding and modeling nonlinear dynamical behavior in cancer immunotherapy and other systems. He serves as a primary resource for clinical trial pharmacokinetics. He has extensive experience in the assessment of adverse drug reactions in the clinical, regulatory and forensic settings, and continues to have responsibilities for such assessments at Georgetown.

Alastair Henry

Author

Alastair immigrated to Canada from England by himself when he was 19. He became a typical yuppie – family, house in the suburbs, and a big job in the corporate sector. Following London Life’s Freedom 55 plan – he retired at 57 and went to live in the country.

A year later, disillusioned with the passivity of retirement, he shed his material possessions and went to live for two years with a small First Nations band in a remote fly-in location in the N.W.T .Cultural differences and a challenging environment ignited in him fresh perspectives, inspired a new way of being, and fueled his soul searching. The experience changed the direction of his life which he wrote about in his memoir: Awakening in the Northwest Territories.

He left the north two years later and, motivated about helping others, went to Bangladesh on a two-year assignment as an International Development volunteer. With his new partner, Candas Whitlock, they next went to Jamaica and Guyana as International Development volunteers on one-year assignments and co-wrote: Go For It – Volunteering Adventures on Roads Less Traveled.

In between volunteering assignments, they backpacked Central America and Southeast Asia for four months at a time and co-wrote: Budget Backpacking for Boomers.

In 2016, they went to Alert Bay, B.C. on a four-month volunteer placement with the Namgis First Nations as part of a Reconciliation Canada project. The experience was so profound they felt compelled to write about it in a memoir entitled: Tides of Change.

Candas and Alastair became entertainers for the next three ye…

Read More

Robert W. Norris

Author

Robert W. Norris was born and raised in Humboldt County, California. He was a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War and served time in a military prison for refusing his order to fight. In his twenties, he roamed across the United States, went to Europe twice, and made one journey around the world. In 1983, he landed in Japan, where he eventually became a professor at a private university and retired as a professor emeritus. He is the author of three novels, a novella, and over 20 research papers on teaching. His most recent book—"The Good Lord Willing and the Creek Don’t Rise: Pentimento Memories of Mom and Me"—is his life story and tribute to his mother. He and his wife live near Fukuoka, Japan.